Exploring Community Health Services for People with Disabilities: An Ethnographic Qualitative Study

Suvapat Nakrukamphonphatn, Khanitta Nuntaboot*

Faculty of Nursing, Khon Kaen University, Muang District, Khon Kaen 40002, Thailand

*Corresponding Author’s Email: khanitta@kku.ac.th

ABSTRACT

Background: Living with a disability often limits individuals’ access to essential healthcare services. Despite this pressing issue, few studies have examined the specific characteristics of community health services needed by People with Disabilities (PWD). This study aims to explore community health services for PWD in the northern region of Thailand. Methods: An ethnographic approach was used to investigate community health services for PWD. A total of 65 informants were selected through purposive sampling, including PWD, family members, healthcare personnel, community leaders, local administrative organization (LAO) officers, volunteers, neighbors, and relatives. Data was collected through in-depth interviews, observations, and document analysis conducted between July 2023 and August 2024. Data was analyzed using thematic analysis. Results: The research identified three main themes related to community health services: (1) self-care including beliefs, cultural wisdom, and Thai traditional medicine; (2) health services—including primary healthcare, rehabilitation, emergency and referral services, long-term care, palliative care, Thai traditional medicine, and volunteer support; and (3) supportive systems, including data management, public services, welfare, and mutual assistance. Conclusion: The study highlights that effective community health services for PWD require collaboration across multiple sectors to ensure equitable access to care. Cultural values and beliefs influence community health services for PWD; therefore, culturally informed approaches should be applied to promote the health of PWD. In addition, welfare policies and supportive systems that enable PWD to access health services should be strengthened.Keywords: Community Health Services; Health Service Access; People with Disabilities (PWD); Self-Care; Supportive Systems

INTRODUCTION

Globally, 1.3 billion people (16%) have disabilities, and this number is increasing due to genetic factors, illness, aging, or accidents (WHO, 2022). Disabilities are classified by type in accordance with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF). People with disabilities (PWD) face a higher risk of dying up to 20 years earlier than the general population and are more vulnerable to health problems. They encounter up to 15 times more restrictions due to limited healthcare access and financial burdens. Their daily lives are further affected by health inequities, discrimination, stigmatization, poverty, exclusion from education and employment, unmet healthcare needs, and poor- quality care (WHO, 2024; Umucu et al., 2025). Persistent disparities in healthcare access leave many behind, resulting in lower life expectancy, poorer health outcomes, and increased vulnerability during health emergencies (WHO, 2022).

In Thailand, 2.22 million people are living with disabilities (Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities, 2025). The proportion of individuals experiencing severe health difficulties increased from 4.1% in 2017 to 4.7% in 2022. Among them, 2% face significant health issues, live in poverty, and lack educational opportunities (National Statistical Office, 2023). Additionally, many experience domestic or community-based violence, and some have attempted suicide (Seesaet et al., 2020). Thailand has adopted measures to ensure a service package for PWD (Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities, 2023). However, many PWD still face substantial barriers to accessing these services due to personal, financial, attitudinal, communication, and other factors (Said et al., 2024; Phutthisrimethi & Lowatcharin, 2020).

The literature review found that Health Promotion Hospitals play a key role in delivering participatory health services within communities (National Health Security Office, 2024). Local Administrative Organizations (LAO) also contribute to improving residents’ quality of life (Ministry of Interior, 2024), but each organization operates within its own defined roles and responsibilities. Thailand’s healthcare policies aim to ensure equitable access to care, including free medical services and a decentralization policy that transfers the management of Health Promotion Hospitals to provincial administrative organizations to strengthen community-level services. Although various types of health services exist, none are directed specifically toward PWD (Ministry of Public Health, 2025).

Culture significantly influences healthcare practices (Duangwises, 2017), and traditional medicine is widely used for rehabilitation and treatment (Department of Medical Services, Ministry of Public Health, 2020). The role of culture is essential in shaping the effectiveness and accessibility of health services for PWD (Hashemi et al., 2022). However, traditional beliefs about illness and the importance of spiritual healing may lead some PWD and their families to delay or avoid seeking formal health services (Pavasuthipaisit et al., 2018).

Cultural stigma surrounding disability can further discourage individuals from utilizing formal care. In addition, family-centered caregiving—a hallmark of Thai culture—while offering emotional support, may inadvertently limit engagement with structured healthcare systems. However, gaps remain in the comprehensive understanding and integration of these practices within the formal healthcare system. This indicates a critical research gap in developing a model that integrates health services. Existing studies provide limited insight into how health services are specifically delivered to PWD. Nurses play a central role in bridging these gaps by coordinating community resources, health services, and relevant policies (Nursing Council of Thailand, 2005).

The complexity of this issue, shaped by social and cultural contexts, aligns with Postmodernist philosophy, which emphasizes interpreting phenomena within their lived environments. Ethnographic research, rooted in anthropology, is designed to examine and understand behaviors within their sociocultural context (Alotaibi, 2018; Creswell & Poth, 2007). It is effective in capturing patient experiences and informing the development of nursing knowledge (Strudwick, 2020). Therefore, an ethnographic qualitative approach can identify disparities and guide improvements in community health services for PWD. This study aims to explore these services to address existing service gaps and contribute to a more inclusive community health system for PWD.

METHODOLOGY

Research Design

This study employed an ethnographic approach to explore the research phenomenon in depth (Hardcastle et al., 2006). The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guidelines were followed to ensure methodological rigor and transparency throughout the study (Tong et al., 2007).

Setting

The study was conducted in a sub-district in northern Thailand, consisting of 12 villages with a total population of 9,384, including 344 individuals with disabilities (3.66%). Most residents work in agriculture, and the primary languages spoken are Lao Wiang and Thai. The community has strong social capital, supported by more than one hundred community-based resources and participatory activities that help reduce health disparities within the local context.

Participants

A total of 65 participants were selected through purposive sampling based on their experience in providing health services, including PWD, family members, healthcare providers, community leaders, LAO officers, volunteers, neighbors, and relatives. Recruitment continued until data saturation was reached. Inclusion criteria required participants to have experience in delivering health services for PWD and to have the ability to communicate. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time, particularly if they felt unwell or unable to continue.

Data Collection

After receiving approval from the Institutional Review Board, data were collected over a 13-month period (July 2023–August 2024). A data collection guideline was developed to ensure consistency throughout the process. Access to data sources was facilitated by a community gatekeeper.

The researcher encompassed both etic and emic perspectives in accordance with the ethnographic method used to comprehensively investigate the values, beliefs, and cultural practices of PWD. The study utilized an ethnographic approach to data collection (Hardcastle et al., 2006).

First phase: Data collection was conducted through observation from both etic and emic perspectives (e.g., daily routines, health services, community events). Fieldwork was carried out one week per month over four months, along with document review (e.g., health records, welfare information) and in-depth interviews.

Second phase: Data analysis began with descriptions of the cultural context and the identification of social interactions and routines. The data were initially coded and categorized.

Third phase: The researcher revisited phases 1–2 in light of new understandings generated through discussions.

Fourth–fifth phases: The findings were compiled and synthesized, then presented in a conceptual framework and documented.

Data Analysis

The study utilized an ethnographic approach (Hardcastle et al., 2006). Thematic analysis was conducted following the framework proposed by Braun and Clarke (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Interviews were transcribed verbatim and reviewed multiple times to ensure familiarity with the content. Data were coded, and similar codes were grouped into categories. Subcategories were refined and merged into broader themes representing participants lived experiences with community health services for PWD. To enhance accuracy and credibility, themes were cross validated by comparing data from interviews, observations, and documents. Findings were confirmed through member checking with local informants and reviewed in consultation with a research advisor.

Methodological Rigor

To ensure rigor throughout the research process, the study strictly adhered to four criteria for trustworthiness: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability (Ahmed, 2024). Credibility was established through prolonged engagement in community activities, persistent observation, and triangulation of data sources (interviews, observations, and documents). Transferability was supported by providing detailed descriptions of participant selection, including participant types and demographic characteristics, allowing the findings to be applied to similar contexts. Dependability was maintained by using multiple data collection methods and clearly outlining the research questions, procedures, and participant details to ensure transparency. Confirmability was achieved through informant feedback, field notes, and expert consultation, helping to minimize potential researcher bias.

Ethical Consideration

This research received ethical approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee of Khon Kaen University, Thailand, with reference number HE662114 on 23rd June, 2023.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Participants

Throughout this study, data was collected from 65 informants who had experience in providing health services. The characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Characteristics of the Participants (N=65)

Participants

Code

Characteristics

Quantity

PWD (n=19)

P1-19

Age

X = 54.52 (SD = 22.66)

Sex

Male

9 (47.36%)

Female

10 (52.63%)

Living

Alone

6 (31.57%)

Family

13 (68.42%)

Income (THB/month)

X = 1.716 (SD = 2,149)

Education

No formal education

10 (52.63%)

Primary school

6 (31.58%)

High-school

3 (15.79%)

ADL (Activities of Daily Life)

0-4 (total-dependence)

5 (26.32%)

5-11(moderately-dependence)

2 (10.53%)

≥12 (independence)

12 (63.16%)

Disease

No underlying disease

9 (47.37%)

Hypertension

6 (31.58%)

Colon cancer (CA)

1 (5.26%)

HIV+

2 (10.53%)

Seize

1 (5.26%)

Family-Caregiver (n=19)

PF1-19

Age

X = 54.22 (SD = 12.83)

Sex

Male

5 (26.32%)

Female

14 (73.68%)

Income

X = 7.379 (SD = 5,446)

Volunteers (n=9)

PV1-9

Age

X = 59.36 (SD = 13.57)

Sex

Male

2 (22.22%)

Female

7 (77.78%)

Healthcare providers (n=6)

PP1-6

Age

X = 38.16 (SD = 9.32)

Professional Roles of Healthcare Providers

PP1-2

Nurse

2 (33.33%)

PP3

Public-health officers

1 (16.67%)

PP4

Dentist

1 (16.67%)

PP5

Director

1 (16.67%)

PP6

Physiotherapist

1 (16.67%)

LAO and Leaders (n=5)

PO1-5

Age

X =53 (SD = 4.14)

Leadership and Administrative Positions

PO1

Head of LAO

1 (20.00%)

PO2-3

Director of division

2 (40.00%)

PO4

Officer

1 (20.00%)

PO5

Head of community

1 (20.00%)

Related people (n=7)

PG1-7

Age

X =55.9 (SD = 18.07)

Community Representatives

PG1-3

Neighbors

3 (42.86%)

PG4

Monk

1 (14.29%)

PG5

Business-owner

1 (14.29%)

PG6

Teacher

1 (14.29%)

PG7

Officer

1 (14.29%)

Thematic Findings

The ethnographic study identified three main themes and 14 sub-themes, highlighting issues related to community health services for PWD (Table 2). The findings are presented in detail, with selected quotes from observations and interviews shown in italics.

Table 2: Thematic Finding

Theme

Sub-themes

Self-Care System

Belief

Thai-traditional-medicine

Cultural wisdom

Health-services-system

Primary care services

Rehabilitation

Emergency medicine and referrals

Long-term care (LTC)

Palliative-care

Thai-traditional-medicine

Volunteers

Supportive-System

Data-utilization

Public services

Government Welfare

Mutual assistance

Theme 1:

Self-Care System: People with disabilities (PWD) manage their daily lives, care for themselves during illness, and maintain their well-being even in the final stages of life by drawing on personal beliefs, cultural wisdom, and traditional Thai medicine.

Belief-Based Practices: Some PWD and their families engage in spiritual and ritual healing practices such as spirit medium ceremonies, sprinkling holy water, and ritualistic blowing to treat unexplained symptoms or illnesses not addressed by conventional medicine. Although not scientifically proven, these practices are deeply rooted in personal and cultural belief systems.

“There was a spirit father who performed a ritual by blowing and bathing me with holy water. At that time, I was in pain and had a headache from something unseen. The hospital couldn’t help, so I turned to a healer. If it’s a spirit mother or spirit father, I recover very quickly.” (P10)

Use of Thai- Traditional- Medicine: Self- care among PWD includes the use of herbal remedies, massage, compress therapy, and herbal steaming to relieve various symptoms. These practices are often passed down through generations and are actively shared within the community.

“I use turmeric to relieve bloating drying it in the sun, grinding it with lime peel. This recipe was passed down to me. I now teach it at Lamduan Waisai School ( senior school) , where we also make herbal compresses, balms, and inhalers.” (P3)

Cultural Wisdom and Local Tools: Cultural wisdom extends to the use of locally adapted tools, community traditions, and physical activities that support health and well- being. These elements empower individuals and foster participation.

“My younger brother made a pulley for me to use at work. Sometimes he helps, sometimes he doesn't— but it helps me stay active.” (P4)

“ I joined in playing Mangkala music, which is supported by the Subdistrict Administrative Organization. It’ s a meaningful activity especially for the elderly because it gives us a chance to perform and participate.” (P10)

Theme 2

Health Services System: When people with disabilities ( PWD) experience health problems such as chronic illness or emergencies they often receive care within their homes. These services are delivered by a multidisciplinary team, including nurses, public health professionals, Thai traditional medicine practitioners, volunteers, and community workers.

Primary Care Services: Comprehensive primary care for PWD includes prevention, treatment, chronic disease management, dental care, antenatal care, family planning, home care, occupational health, and traditional Thai medicine. Services are delivered through both reactive ( clinic- based) and proactive (outreach) approaches.

“...Chronic diseases and common illnesses, like mild sore throats, are managed with medication, often collected by relatives. For blood pressure monitoring, we offer home services, check- ups, in severe cases, referrals are issued, primarily for emergencies requiring further treatment. Every disease follows a Clinical Practice Guideline from the hospital.” (PP1)

Rehabilitation: Rehabilitation services are available in hospitals, community centers, and homes, but there are no standardized programs specifically designed for PWD. Analysis highlighted four key aspects: 1) Integration of traditional Thai medicine and family/ community participation in rehabilitation, 2) Capacity-building for caregivers and community rehabilitation volunteers, 3) Access to assistive devices through community equipment centers and 4) Development of an integrated rehabilitation data system.

“ Rehabilitation programs for PWD are not standardized but are tailored to individual needs, with a strong emphasis on mobility. If patients cannot travel to the hospital, services are provided at the community level, though the frequency varies...” (PP6)

Emergency Medicine and Referrals: Emergency services include ambulance transport, general support vehicles, and first-response care. Community fundraising and volunteer training in life-saving techniques enhance service sustainability.

“…He fainted. No one would have noticed at night, but someone saw and called an ambulance to take him to the hospital for treatment.” (P4)

“We raise money to fund projects, buy fuel, provide aid, and keep a reserve fund.” (PO1)

Long- Term- Care ( LTC): LTC services target individuals with ADL scores below 11, indicating moderate to total dependence. Care involves collaboration among health personnel, LAO officers, and community volunteers.

“They come to take care of me—bringing me diapers, cleaning me, and helping with self-care at home. It’ s good. Some use traditional Thai massage and herbal compresses, which make me feel better. ” (P12)

Palliative-Care: Palliative-Care is provided for patients, especially those with terminal cancer, includes pain management, home visits, and emotional support for both patients and families.

“Cancer patients will receive palliative care. If sent home, a syringe driver is provided, and caregivers manage wound care. In most cases, psychological support is also crucial.” (PP2)

Thai- Traditional- Medicine: This includes herbal steaming, massage, compresses, and home- grown herbal remedies. These practices are supported through community training and demonstrations.

“They teach us how to make compresses and balms, and how to grow and use herbs at home. I soak my feet and apply herbs to my knees.” (P5)

Volunteer Support: Volunteers are trained by Hospital and Health Promotion Hospital to support care for PWD, including basic rehabilitation, physical therapy techniques, promote- health, and connect between government sector and PWD.

“ Subdistrict Health Promoting Hospital trains us to care for patients, not just those with disabilities but also those needing rehab. I’ve learned a lot and plan to attend more sessions.” (PV4)

Theme 3

Supportive- System: The supportive system for PWD in the community encompasses data management, public services, government welfare, and mutual assistance mechanisms. These systems are implemented through collaboration between governmental agencies, local administrative bodies, and the community.

Data Systems and Utilization: Data systems used to support PWD are developed and managed by both government agencies and local communities. These include the collection, analysis, and application of disability-related information to coordinate services.

“... There is a survey of PWD, but it is not comprehensive. The village community knows who has specific needs, and while we have collected data, it is mainly part of a welfare database. Local records help monitor allowances and support...” (PO2)

Public Services: Public services include transportation assistance, educational support for children with disabilities, health promotion initiatives, cultural programs, and environmental improvements. These services help PWD participate more fully in community life.

“...I get my blood pressure checked regularly. If I need to go to the hospital, I ask my younger brother to notify the Subdistrict Administrative Organization, and they arrange a car for me.” (P7)

Government Welfare: The government provides a range of welfare benefits to PWD, including monthly allowances, personal assistants, home modifications, career development, health coverage, vocational- rehabilitation, restore- daily- life rehabilitation, and educational- support. Welfare is administered through both centralized and local systems.

“ I receive my disability benefits on time from the Subdistrict Administrative Organization. It really helps—without them, life would be very difficult. I haven’t been able to work since falling ill.” (P4)

Mutual Assistance in the Community: Leader, community-members, club, community-organization, monk, and volunteers provide informal support by donating money, materials, food, career- promote, daily- living- assistance, volunteering their time for home repairs and caregiving, and setting up an equipment-center for donations, where PWD can borrow and return equipment.

“The merit group donated money to help repair houses for PWD, and volunteer technicians also helped with the repairs.” (P6)

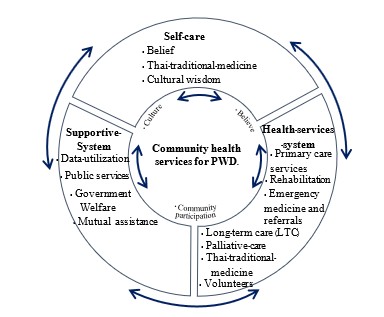

Based on the research results, conceptualized the framework of community health services for PWD as presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Conceptual Framework of Community Health Services for PWD

DISCUSSION

The research identified three main themes related to community health services: Self-Care, Health Services, and Support System, which interact with one another (Figure1). Government health services in Thailand provide both reactive and proactive care consistent with public policy frameworks. However, specific programs tailored to the unique needs of PWD are lacking. Although Thailand offers universal health coverage (Ministry of Public Health, 2023; Office of the Decentralization to the Local Government Organization Committee, 2022), it does not include travel costs, accommodation, or essential assistive equipment—barriers that limit actual access to care (Muñoz et al., 2016; Ekakkararungroj et al., 2024). Moreover, healthcare providers often exercise decision-making authority over PWD, such as choosing therapy types or service locations, which further limits autonomy. Therefore, to improve access to health services for PWD, it is necessary to identify individuals and provide care based on their specific problems and needs.

Self-care among PWD reflects a blend of traditional wisdom, spiritual beliefs, and cultural healing practices such as spirit rituals and Thai traditional medicine. While these practices play a valuable role in symptom relief and personal empowerment (Duangwises, 2017), they also present limitations, including slow-acting effects, a lack of formal dosage standards, and limited capacity to treat severe conditions. This imbalance often leads to overreliance on modern medical professionals, who may overlook cultural practices when delivering care (Department of Medical Services, Ministry of Public Health, 2020). To address these issues, nurses play a crucial role as change agents, supporting PWD and caregivers in managing medications, attending appointments, and preventing complications. This approach aligns with Orem’s Self-Care Deficit Nursing Theory, which advocates nurse-led support when individuals are unable to fully care for themselves (Parker & Smith, 2010). However, the shortage of medical personnel remains a challenge for the government sector, though volunteers have been mobilized to help fill this gap.

Improving access to healthcare also requires the strategic use of data systems, public services, and government welfare programs. While data collection is underway in Thailand, it remains fragmented and inconsistent, reducing its effectiveness (Phutthisrimethi & Lowatcharin, 2020). In contrast, countries like Australia have developed national health data systems (e.g., My Health Record) to manage PWD information (Australian Digital Health Agency, 2025). In terms of public services and

welfare, many developed countries apply universal design principles and the welfare state model to ensure comprehensive support for PWD (Gugushvili et al., 2023; European Commission, 2024). Thailand has universal policies, but local infrastructure and budget limitations hinder their implementation. These challenges have led communities to rely on mutual aid efforts, such as fundraising and volunteer networks, to fill service gaps. In response, nurses can foster partnerships with local leaders, government bodies, and civil society organizations to enhance healthcare access. Their role is key in connecting PWD to essential resources such as transportation, financial assistance, and public benefits, thereby ensuring equitable, culturally sensitive, and community-based care (Zulpiani & Rusyani, 2023).

The results highlight that community health services for PWD require the integration of three core components. This model aligns with community- based rehabilitation for older adults’ post- stroke consisting of supportive systems, social and economic support, and administrative and management systems ( Somtua & Nuntaboot, 2025). As supported by systems theory ( Smith- Acuña, 2011), these elements cannot function in isolation but must operate in dynamic interconnection to effectively support vulnerable populations. In alignment with the health commitments of stakeholders for PWD ( International Disability Alliance, 2025) , Thailand has implemented a participatory policy to promote the quality of life for PWD. However, operations remain fragmented; while assistance from the public sector enables implementation at the local level, it is not yet comprehensive.

Limitations

This study had certain limitations. As it focused on exploring the cultural context of care for PWD within a specific community, the applicability of the findings to other cultural settings requires further investigation.

CONCLUSION

Community health services for PWD are most effective when built upon the integration of three core components ( figure 1). These components form a comprehensive framework that ensures equitable access to healthcare and promotes the overall well- being of PWD. Effective implementation requires collaboration among key entities: Health Promotion Hospitals, LAOs, community leaders, and etc. Culture need to integrate practices, organizational functions, and community group to ensure the effective and tangible implementation of nursing interventions.

The Implication for nursing practice is to integrate the framework to improve nursing care on culture values. Early intervention and support for PWD should prioritize their culture belief by enhancing specialized healthcare delivery. This includes expanding home- based care, incorporating nursing technologies, and promoting framework with flexible care guidelines tailored to individual needs. For health policy development, there should be collaboration with local governments and community organizations to ensure comprehensive health care. Moreover, local resources should be utilized to ensure the provision of holistic. Further research should focus on developing a culturally adaptive framework of community health services for PWD to enhance nursing care.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest related to this study.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to express their heartfelt gratitude to all informants who generously shared their experiences and insights throughout this study.

REFERENCES

Alotaibi, N.N.M. (2018). Ethnography in qualitative research: A literature review. International Journal of Education, 10(3), 25-35. https://doi.org/10.5296/ije.v10i3.13209

Australian Digital Health Agency. (2025). My Health Record. https://www.digitalhealth.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/my-health-record

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage publications.

Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities. (2023). Rights/Welfare/Services. https://dep.go.th/th/rights-welfares-services

Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities. (2025). Situation of people with disabilities. https://dep.go.th/images/Dep0225688.pdf

Department of Medical Services, Ministry of Public Health. (2020). Manual for palliative and end-of- life patient care (for medical personnel). Nonthaburi. War Veterans Organization. http://www.ppb.moi.go.th/midev05/upload/26.01.77.pdf.

Duangwises, N. (2017). แนวคิดมานุษยวิทยากบั การศึกษาความเชื่อสิ่งศกั ด์ิสิทธ์ิในสังคมไทย [Anthropological Concepts and the Studies of Animistic Beliefs in Thai Society]. Academic Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Burapha University, 25(47), 173-197. https://so06.tci-

thaijo.org/index.php/husojournal/article/view/76724/61652

Ekakkararungroj, C., Chareonrungrueangchai, K. Rachatan, C., Pratumsuwan, S. Saeraneesophon, T. Kittibovorndit, N. & Teerawattananon, Y. (2024). กรณีศึกษาการวิเคราะห์ตน้ ทุนบริการสุขภาพปฐมภูมิ เปรียบเทียบระหว่างโรงพยาบาลส่งเสริมสุขภาพตาํ บล ถ่ายโอนแก่องคก์ รปกครองส่วนทอ้ งถิ่นและที่คงสังกด กระทรวงสาธารณสุข [A Comparative Analysis of Primary Care Costs of Sub-District Health Promoting Hospitals of Local Governments and of Ministry of Public Health]. Journal of Health Systems Research, 18(1), 49-59. https://kb.hsri.or.th/dspace/bitstream/handle/11228/6040/hsri-journal- v18n1-p49-59.pdf?sequence=1&a…

European Commission. Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion. (2024). Social Protection & Social Inclusion. https://employment-social-affairs.ec.europa.eu/index_en

Gugushvili, A., Grue, J., Dokken, T., & Finnvold, J. E. (2023). No evidence that social-democratic welfare states equalize valued outcomes for individuals with disabilities. Social Science & Medicine, 339, 116361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.116361

Hardcastle M-A, Usher K, Holmes, C. (2006). Carspecken’s Five-Stage Critical Qualitative Research Method: An application to nursing research. Qualitative Health Research, 16(1), 151- 161. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305283998

Hashemi, G., Wickenden, M., Bright, T., & Kuper, H. (2022). Barriers to accessing primary healthcare services for people with disabilities in low and middle-income countries, a Meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(8), 1207-1220. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1817984

International Disability Alliance. (2025). Global Disability Summit 2025. https://www.globaldisabilitysummit.org/

Ministry of Interior. (2024). A guide to improving the quality of life for people of all ages (from the mother’s womb to the sediment bed) at the local level. http://www.ppb.moi.go.th/midev05/upload/26.01.77.pdf

Ministry of Public Health. (2023). Primary Health Service Standards Manual 2023. https://www.dndpho.org/attachments/view/?attach_id=381474

Ministry of Public Health. (2025). Guidelines for collecting nursing service quality development indicators: 2025. https://www.don.go.th/Doc_download/2568/2024-11-21/D0010.pdf

Muñoz, D. C., Amador, P. M., Llamas, M. L., Hernandez, D. M., & Sancho, J. M. S. (2016). Decentralization of health systems in low and middle-income countries: A systematic review. International Journal of Public Health, 62(2), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-016- 0872-2

National Health Security Office. (2024). Long term care. https://ltcnew.nhso.go.th/#

National Statistical Office. (2023). The 2022 Disability Survey [Survey]. Statistical Forecasting Division. https://www.unicef.org/thailand/media/11376/file/Disability%20Survey%20Report%20202 2.pdf

Nursing Council of Thailand. (2005). ประกาศสภาการพยาบาล เรื่อง มาตรฐานการบริการพยาบาลและการผดุงครรภ ในระดบั ปฐมภูมิ. [Announcement of the Nursing Council on the standards of nursing and midwifery services in primary care] (Announcement in the Government Gazette, Vol. 122, Part 62). Government

Gazette. https://www.tnmc.or.th/images/userfiles/files/P123.PDF

Office of the Decentralization to the Local Government Organization Committee (2022). Guidelines for carrying out mission transfers: Chaloem Phrakiat 60th Anniversary Nawamintharachini Health Station and Sub-district Health Promotion Hospital for the Provincial Administrative Organization. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1aIdKh0TwdEiVLRlHB5Jdm95EFAKHyhAF/view

Parker. M.E., & Smith, M.C. (2006). Nursing theories and nursing practice. (3rd Edition). Philadelphia. Devis. https://philpapers.org/rec/PARNTA

Pavasuthipaisit, C., Sringernyuang, L., Asavaroungpipop, N., Booranasuksakul, T., Chaninyuthwong, V., Panyawong, W., & Sriwilas, T. (2018). Situation of disability and access to essential public services of children with disabilities in the community of Thailand. Journal of Health Systems Research, 12(3), 469-479. https://kb.hsri.or.th/dspace/handle/11228/4942

Phutthisrimethi, P., & Lowatcharin, G. (2020). ศกั ยภาพ ใน การ พัฒนา คุณภาพ ชีวิต คน พิการ ของ องค์กร ปกครอง ทอ้ งถ่ิน ใน จงั หวัด ขอนแก่น [Potential for improving the quality of life of people with disabilities in local government organizations in Khon Kaen Province]. Journal of Buddhist Education and Research (JBER), 6(1), 301-312. https://so06.tci- thaijo.org/index.php/jber/article/view/242742

Said, A. H., Mohd, F. N., Baharom, M. Z., Aris, M. A., & Shahrin, M. A. (2024). Barriers towards healthcare access and services among PWD: A scoping review of qualitative studies. International Medical Journal Malaysia, 23(4), 20-28. https://doi.org/10.31436/imjm.v23i04.2460

Seesaet, S., Auemaneekul, N., Lagampan, S., & Sujirarat, D. (2020). Violence against persons with mobility or physical disabilities and related factors in Samut Prakan Province. Kuakarun Journal of Nursing, 27(2), 116-129. https://he01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/kcn/article/view/179149/167084

Smith-Acuña, S. (2010). Systems theory in action: Applications to Individual, Couple, and Family Therapy. John Wiley & Sons.

Somtua, N., & Nuntaboot, K. (2025). Community-based rehabilitation for older adults’ post-stroke in Thailand: An ethnographic study. Belitung Nursing Journal, 11(2), 205. https://doi.org/10.33546/bnj.3690

Strudwick, R. M. (2021). Ethnographic research in healthcare–patients and service users as participants. Disability and Rehabilitation, 43(22), 3271-3275. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1741695

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349-357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

Umucu, E., Vernon, A. A., Pan, D., Qin, S., Solis, G., Campa, R., & Lee, B. (2025). Health inequities among persons with disabilities: A global scoping review. Frontiers in Public Health, 13, 1538519. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1538519

World Health Organization (WHO). (2022). Global report on health equity for persons with disabilities. Geneva. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240063600

World Health Organization (WHO). (2024). Disability. https://www.who.int/health- topics/disability#tab=tab_1

Zulpiani, M., & Rusyani, E. (2023). Application of universal design principles in public spaces for persons with disabilities. Journal of ICSAR, 7(1), 18- 22. http://dx.doi.org/10.17977/um005v7i12023p18

Participants

Code

Characteristics

Quantity

PWD (n=19)

P1-19

Age

X = 54.52 (SD = 22.66)

Sex

Male

9 (47.36%)

Female

10 (52.63%)

Living

Alone

6 (31.57%)

Family

13 (68.42%)

Income (THB/month)

X = 1.716 (SD = 2,149)

Education

No formal education

10 (52.63%)

Primary school

6 (31.58%)

High-school

3 (15.79%)

ADL (Activities of Daily Life)

0-4 (total-dependence)

5 (26.32%)

5-11(moderately-dependence)

2 (10.53%)

≥12 (independence)

12 (63.16%)

Disease

No underlying disease

9 (47.37%)

Hypertension

6 (31.58%)

Colon cancer (CA)

1 (5.26%)

HIV+

2 (10.53%)

Seize

1 (5.26%)

Family-Caregiver (n=19)

PF1-19

Age

X = 54.22 (SD = 12.83)

Sex

Male

5 (26.32%)

Female

14 (73.68%)

Income

X = 7.379 (SD = 5,446)

Volunteers (n=9)

PV1-9

Age

X = 59.36 (SD = 13.57)

Sex

Male

2 (22.22%)

Female

7 (77.78%)

Healthcare providers (n=6)

PP1-6

Age

X = 38.16 (SD = 9.32)

Professional Roles of Healthcare Providers

PP1-2

Nurse

2 (33.33%)

PP3

Public-health officers

1 (16.67%)

PP4

Dentist

1 (16.67%)

PP5

Director

1 (16.67%)

PP6

Physiotherapist

1 (16.67%)

LAO and Leaders (n=5)

PO1-5

Age

X =53 (SD = 4.14)

Leadership and Administrative Positions

PO1

Head of LAO

1 (20.00%)

PO2-3

Director of division

2 (40.00%)

PO4

Officer

1 (20.00%)

PO5

Head of community

1 (20.00%)

Related people (n=7)

PG1-7

Age

X =55.9 (SD = 18.07)

Community Representatives

PG1-3

Neighbors

3 (42.86%)

PG4

Monk

1 (14.29%)

PG5

Business-owner

1 (14.29%)

PG6

Teacher

1 (14.29%)

PG7

Officer

1 (14.29%)

Thematic Findings

Theme

Sub-themes

Self-Care System

Belief

Thai-traditional-medicine

Cultural wisdom

Health-services-system

Primary care services

Rehabilitation

Emergency medicine and referrals

Long-term care (LTC)

Palliative-care

Thai-traditional-medicine

Volunteers

Supportive-System

Data-utilization

Public services

Government Welfare

Mutual assistance